Frank Gehry

Frank Gehry | |

|---|---|

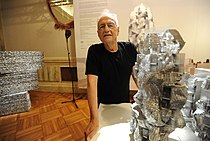

Gehry in 2010 | |

| Born | Frank Owen Goldberg February 28, 1929 Toronto, Ontario, Canada |

| Citizenship |

|

| Education | University of Southern California (B.Arch) |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 4 |

| Awards | List of awards |

| Practice | Gehry Partners, LLP |

| Buildings | List of works |

| Website | foga |

Frank Owen Gehry CC FAIA (/ˈɡɛəri/ GAIR-ee; né Goldberg; born February 28, 1929) is a Canadian-American architect and designer. A number of his buildings, including his private residence in Santa Monica, California, have become attractions.

He rose to prominence in the 1970s with his distinctive style that blended everyday materials with complex, dynamic structures. Gehry's approach to architecture has been described as deconstructivist, though he himself resists categorization. His works are considered among the most important of contemporary architecture in the 2010 World Architecture Survey, leading Vanity Fair to call him "the most important architect of our age".[2] Gehry is known for his postmodern designs and use of bold, unconventional forms and materials. His most famous works include the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao in Spain, the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, and the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris, and the National Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial in Washington D.C[3] These buildings are characterized by their sculptural, often undulating exteriors and innovative use of materials such as titanium and stainless steel.

Throughout his career, Gehry has received numerous awards and honors, including the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 1989, considered the field's highest honor. He has also been awarded the National Medal of Arts and the Presidential Medal of Freedom in the United States. Gehry's influence extends beyond architecture; he has designed furniture, jewelry, and liquor bottles.

Early life

[edit]

Frank Owen Gehry was born Frank Owen Goldberg on February 28, 1929, in Toronto, Ontario,[4][5] to parents Sadie Thelma (née Kaplanski/Caplan) and Irving Goldberg.[6] His American father was born in New York City to Russian-Jewish parents, and his Polish-Jewish mother was an immigrant born in Łódź, Poland.[7][8][9] A creative child, he was encouraged by his grandmother, Leah Caplan,[10] with whom he built little cities out of scraps of wood.[11] With these scraps from her husband's hardware store, she entertained him for hours, building imaginary houses and futuristic cities on the living room floor.[6]

Gehry's use of corrugated steel, chain-link fencing, unpainted plywood, and other utilitarian or "everyday" materials was partly inspired by spending Saturday mornings at his grandfather's hardware store. He spent time drawing with his father, and his mother introduced him to the world of art. "So the creative genes were there", Gehry says. "But my father thought I was a dreamer, I wasn't gonna amount to anything. It was my mother who thought I was just reticent to do things. She would push me."[12]

He was given the Hebrew name "Ephraim" by his grandfather, but used it only at his bar mitzvah.[13] In 1954, Gehry changed his surname from Goldberg to Gehry, after his then-wife Anita expressed concern about antisemitism.[14]

Education

[edit]In 1947, Gehry's family immigrated to the United States, settling in California. He got a job driving a delivery truck and studied at Los Angeles City College.

According to Gehry, "I was a truck driver in L.A., going to City College, and I tried radio announcing, which I wasn't very good at. I tried chemical engineering, which I wasn't very good at and didn't like, and then I remembered. You know, somehow I just started wracking my brain about, 'What do I like?' Where was I? What made me excited? And I remembered art, that I loved going to museums and I loved looking at paintings, loved listening to music. Those things came from my mother, who took me to concerts and museums. I remembered Grandma and the blocks, and just on a hunch, I tried some architecture classes."[15]

Gehry went on to graduate from the University of Southern California's School of Architecture in 1954. During that time, he became a member of Alpha Epsilon Pi.[16][17] He then spent time away from architecture in numerous other jobs, including service in the United States Army.[11] In the fall of 1956, he moved his family to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he studied city planning at Harvard University's Graduate School of Design. Gehry had always expressed an socialist philosophy for architecture, something that was influenced by political views as he expressed a more leftist attitude to the world. These progressive ideas about socially responsible architecture were under-realized and not respected by his professors at Harvard, leaving him to feel disheartened and "underwhelmed".[18] Gehry's distaste for the school culminated after he was invited by his architecture professor to engage in a discussion revolving around a "secret architectural project in progress." Which was ultimately revealed to Gehry as a palace that he was designing for Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista.[6][19]

Career

[edit]

Gehry ultimately dropped-out of his graduate program at Harvard to start a furniture manufacturing company Easy Edges, which specialised in creating pieces with cardboard.

He returned to Los Angeles to work for Victor Gruen Associates, with whom he had apprenticed while at USC. In 1957, at age 28, he was given the chance to design his first private residence with friend and old classmate Greg Walsh. Construction was done by another neighbor across the street from his wife's family, Charlie Sockler. Built in Idyllwild, California for his wife Anita's family neighbor Melvin David, the over 2,000 sq ft (190 m2) "David Cabin"[20] shows features that were to become synonymous with Gehry's later work, including beams protruding from the exterior sides, vertical-grain douglas fir detail, and exposed unfinished ceiling beams. It also shows strong Asian influences, stemming from his earliest inspirations, such as the Shōsōin in Nara, Japan.

In 1961, Gehry moved to Paris, where he worked for architect Andre Remondet.[21] In 1962, he established a practice in Los Angeles that became Frank Gehry and Associates in 1967,[11] then Gehry Partners in 2001.[22] His earliest commissions were in Southern California, where he designed a number of innovative commercial structures such as Santa Monica Place (1980) and residential buildings such as the eccentric Norton House (1984) in Venice, Los Angeles.[23]

Among these works, Gehry's most notable design may be the renovation of his own Santa Monica residence.[24] Originally built in 1920 and purchased by Gehry in 1977, it features a metallic exterior wrapped around the original building that leaves many of the original details visible.[25] Gehry still resides there.

Other of Gehry's buildings completed during the 1980s include the Cabrillo Marine Aquarium (1981) in San Pedro, and the California Aerospace Museum (1984) at the California Museum of Science and Industry in Los Angeles.

In 1989, Gehry received the Pritzker Architecture Prize, where the jury described him: "Always open to experimentation, he has as well a sureness and maturity that resists, in the same way that Picasso did, being bound either by critical acceptance or his successes. His buildings are juxtaposed collages of spaces and materials that make users appreciative of both the theatre and the back-stage, simultaneously revealed."[26]

Gehry continued to design other notable buildings in California, such as the Chiat/Day Building (1991) in Venice, in collaboration with Claes Oldenburg, which is well known for its massive sculpture of binoculars. He also began receiving larger national and international commissions, including his first European commission, the Vitra International Furniture Manufacturing Facility and Design Museum in Germany, completed in 1989. It was soon followed by other major commissions including the Frederick Weisman Museum of Art[27] (1993) in Minneapolis, Minnesota; the Cinémathèque Française[28](1994) in Paris, originally The American Center in Paris;[29] and the Dancing House[30] (1996) in Prague.

From 1994 to 1996 a couple buildings by Gehry for a Public housing project were realized in Goldstein, part of Frankfurt-Schwanheim (1994) In 1997, Gehry vaulted to a new level of international acclaim[2] when the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao opened in Bilbao, Spain. Hailed by The New Yorker as a "masterpiece of the 20th century", and by legendary architect Philip Johnson as "the greatest building of our time",[31] the museum became famous for its striking yet aesthetically pleasing design and its positive economic effect on the city.

Since then, Gehry has regularly won major commissions and established himself as one of the world's most notable architects. His best-received works include several concert halls for classical music. The boisterous, curvaceous Walt Disney Concert Hall (2003) in downtown Los Angeles is the centerpiece of the neighborhood's revitalization; the Los Angeles Times called it "the most effective answer to doubters, naysayers, and grumbling critics an American architect has ever produced".[32] Gehry also designed the open-air Jay Pritzker Pavilion (2004) in Chicago's Millennium Park;[33] and the understated New World Center (2011) in Miami Beach, which the LA Times called "a piece of architecture that dares you to underestimate it or write it off at first glance."[34]

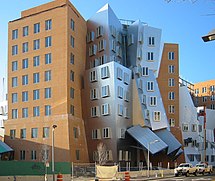

His other notable works include academic buildings such as the Stata Center (2004)[35] at MIT, and the Peter B. Lewis Library (2008) at Princeton University;[36] museums such as the Museum of Pop Culture (2000) in Seattle, Washington;[37] commercial buildings such as the IAC Building (2007) in New York City;[38] and residential buildings, such as Gehry's first skyscraper, the Beekman Tower at 8 Spruce Street (2011)[39] in New York City.

Gehry's recent major international works include the Dr Chau Chak Wing Building at the University of Technology Sydney, completed in 2014,[40] and the Chau Chak Wing, with its 320,000 bricks in "sweeping lines", described as "10 out of 10" on a scale of difficulty.[41] An ongoing project is the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi on Saadiyat Island in the United Arab Emirates.[42] Other significant projects such as the Mirvish Towers in Toronto,[43] and a multi-decade renovation of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, are currently in the design stage. In October 2013, Gehry was appointed joint architect with Foster + Partners to design the High Street phase of the development of Battersea Power Station in London, Gehry's first project there.[44]

In recent years, some of Gehry's more prominent designs have failed to go forward. In addition to unrealized designs for the Corcoran Art Gallery expansion in Washington, DC, and a new Guggenheim museum near the South Street Seaport in New York City, Gehry was notoriously dropped by developer Bruce Ratner from the Pacific Park (Brooklyn) redevelopment project, and in 2014 as the designer of the World Trade Center Performing Arts Center in New York City.[45] Some stalled projects have recently shown progress: After many years and a dismissal, Gehry was recently reinstated as architect for the Grand Avenue Project in Los Angeles, and though his controversial[46][47][48] design of the National Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial in Washington, DC has had numerous delays during the approval process with the United States Congress, it was finally approved in 2014 with a modified design.

In 2014, two significant, long-awaited museums designed by Gehry opened: the Biomuseo,[49] a biodiversity museum in Panama City, Panama; and the Fondation Louis Vuitton,[50][51][52] a modern art museum in the Bois de Boulogne park in Paris, France, which opened to some rave reviews.[53]

Also in 2014, Gehry was commissioned by River LA (formerly the Los Angeles River Revitalization Corporation), a nonprofit group founded by the city of Los Angeles in 2009 to coordinate river policy, to devise a wide-ranging new plan for the river.[54][55]

In February 2015, the new AU$180 million building for the University of Technology Sydney was officially opened, whose façade has more than 320,000 hand-placed bricks and glass slabs. Gehry said he would not design a building like the "crumpled paper bag" again.[56]

Gehry told the French newspaper La Croix in November 2016 that President of France François Hollande had assured him he could relocate to France if Donald Trump was elected President of the United States.[57][58] The following month, Gehry said that he had no plans to move.[59] Trump and he exchanged words in 2010 when Gehry's 8 Spruce Street, originally known as Beekman Tower, was built 1 foot (0.30 m) taller than the nearby Trump Building, which until then was New York City's tallest residential building.[58][60]

Notable Gehry-designed buildings completed in the 2020s include the Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial in Washington, DC[61] and the LUMA Arles museum in France.[62] In 2021, noting Gehry's progress on an increasing number of significant projects in his hometown, including the Grand Avenue Project, a concert hall for the Youth Orchestra Los Angeles, and an office building for Warner Bros., The Architect's Newspaper stated that "Seventy-four years after he moved there from his native Toronto, L.A. is looking more and more like Gehry Country."[63]

Architectural style

[edit]Said to "defy categorisation", Gehry's work reflects a spirit of experimentation coupled with a respect for the demands of professional practice, and has remained largely unaligned with broader stylistic tendencies or movements.[64] With his earliest educational influences rooted in modernism, Gehry's work has sought to escape modernist stylistic tropes while remaining interested in some of its underlying transformative agendas. Continually working between given circumstances and unanticipated materializations, he has been assessed as someone who "made us produce buildings that are fun, sculpturally exciting, good experiences", although his approach may become "less relevant as pressure mounts to do more with less".[64]

Gehry's style at times seems unfinished or even crude, but his work is consistent with the California "funk" art movement of the 1960s and early 1970s, which featured the use of inexpensive found objects and nontraditional media such as clay to make serious art.[65] His works always have at least some element of deconstructivism;[66] he has been called "the apostle of chain-link fencing and corrugated metal siding".[67] However, a retrospective exhibit at New York's Whitney Museum in 1988 revealed that he is also a sophisticated classical artist who knows European art history and contemporary sculpture and painting.[65]

Early influences and design philosophy

[edit]Frank Gehry has often described architecture as inherently sculptural, asserting, “I always thought that architecture was, by definition, a three-dimensional object, therefore sculpture.” This perspective reflects his commitment to blending artistic and architectural disciplines. Gehry’s early work with sculptors influenced his experimental approach, which includes deconstructing traditional architectural forms and embracing ideas of flow and defamiliarization, akin to Viktor Shklovsky’s concept of “laying bare the device.” Critics often describe his work as embodying structuralism rather than traditional formalism.

Cultural and personal influences

[edit]Gehry’s Jewish heritage and immigrant background have shaped his architectural philosophy. He often reinterprets traditional forms in ways that reflect his multicultural experience. His works have been described as embodying “a critique of consumerism” [68]by defying expectations of luxury and focusing on creativity. For Gehry, architecture is not just about creating buildings but about crafting spaces that inspire and challenge societal norms.

Material innovation

[edit]A hallmark of Gehry’s style is his innovative use of materials. He challenges architectural norms by incorporating unconventional elements such as corrugated steel, chain-link fencing, and plywood. His works are celebrated for their “raw aesthetic”[69] that combines everyday materials in unexpected ways, creating structures that blur the line between functionality and artistry. These material choices also reflect a critique of luxury, emphasizing creativity over opulence.

Gallery

[edit]-

Former Rouse Headquarters in Columbia, MD (1974)

-

Merriweather Post Pavillion in Columbia, MD (1967)

-

"El Peix", fish sculpture in front of the Port Olímpic in Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain (1992)

-

Dancing House in Prague (1996)

-

The Museum of Pop Culture in Seattle (2000)

-

Gehry Tower in Hanover, Germany (2001)

-

Weatherhead School of Management, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio (2002)

-

Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles (2003)

-

Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York (2003)

-

Stata Center, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts (2004)

-

BP Pedestrian Bridge, Millennium Park, Chicago (2004)

-

MARTa Herford, Herford, Germany (2005)

-

Hotel Marqués de Riscal in Elciego, Spain (2006)

-

Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Ontario, Canada (2008)

-

Gallery of African American Art, Ohr-O'Keefe Museum Of Art campus in Biloxi, Mississippi (2010)

-

Dr Chau Chak Wing Building in Sydney, Australia (2014)

-

Biomuseo in Panama City (2014)

-

David Cabin – Idyllwild CA (1957)

-

Neuer Zollhof - Dusseldorf, Germany (1998)

-

Energie-Forum-Innovation in Bad Oeynhausen, Germany (1995)

-

Toledo Museum of Art Center for Visual Arts in Toledo, Ohio

-

Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health in Las Vegas (2010)

-

The Grand and Conrad hotel in Los Angeles

Bilbao effect

[edit]

The term "Bilbao Effect" emerged in urban planning to describe the transformative impact of Gehry’s architecture. His design for the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, revitalized the city, serving as a prime example of how architecture can drive economic and cultural renewal. The museum’s dramatic curves and shimmering titanium panels are defining features of Gehry’s style, emphasizing movement and fluidity.

After the phenomenal success of Gehry's design for the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, critics began referring to the economic and cultural revitalization of cities through iconic, innovative architecture as the "Bilbao effect".[70] In the first 12 months after the museum was opened, an estimated US$160 million were added to the Basque economy. Indeed, over $3.5 billion have been added to the Basque economy since the building opened.[71] In subsequent years there have been many attempts to replicate this effect through large-scale eye-catching architectural commissions that have been both successful and unsuccessful, such as Daniel Libeskind's expansion of the Denver Art Museum and buildings by Gehry himself, such as the almost universally well-received Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles and the more controversial Museum of Pop Culture in Seattle.[72] Though some link the concept of the Bilbao effect to the notion of starchitecture, Gehry has consistently rejected the label of a starchitect.[73]

Time management and client interaction

[edit]Despite the complexity of his designs, Gehry’s approach to project management is highly disciplined. He has been praised for listening closely to clients and translating their needs into visionary designs. As one collaborator noted, “Sometimes he produces something for the client that they don’t realize they want because he listens so well.”[74] Gehry himself credits curiosity as a cornerstone of his process, stating, “You’re being curious. And that curiosity leads to invention.” [75]

Criticism

[edit]Though much of Gehry's work has been well-received, its reception was not always positive. Art historian Hal Foster reads Gehry's architecture as, primarily, in the service of corporate branding.[76] Criticism of his work includes complaints over design flaws that the buildings waste structural resources by creating functionless forms, do not seem to belong in their surroundings or enhance the public context of their locations, and are apparently designed without taking into account the local climate.[77][78][79]

Moreover, socialist magazine Jacobin pointed out that Gehry's work can be summed up as architecture for the super-wealthy, in the sense that it is expensive, not resourceful, and does not serve the interests of the overwhelming majority. The article criticized Gehry's statement, "In the world we live in, 98 percent of what gets built and designed today is pure shit".[80]

Academia and design career

[edit]Academia

[edit]In January 2011, Gehry joined the University of Southern California (USC) faculty, as the Judge Widney Professor of Architecture.[81] He has since continued in this role at his alma mater. He has also held teaching positions at Harvard University, the University of California at Los Angeles, the University of Toronto, Columbia University, the Federal Institute of Technology in Zürich, and at Yale University, where he still teaches as of 2017.[82]

Though he is often referred to as a "starchitect", he has repeatedly expressed his disdain for the term, insisting he is only an architect.[73][83] Steve Sample, President of the University of Southern California, told Gehry that "...After George Lucas, you are our most prominent graduate".

As of December 2013[update], Gehry has received over a dozen honorary university degrees (see #Honorary doctorates).

In February 2017, MasterClass announced an online architecture course taught by Gehry that was released that July.[84]

Exhibition design

[edit]Gehry has been involved in exhibition designs at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art dating back to the 1960s. In 1965, Gehry designed the exhibition display for the "Art Treasures of Japan" exhibition at the LACMA. This was followed soon after by the exhibition design for the "Assyrian Reliefs" show in 1966 and the "Billy Al Bengston Retrospective" in 1968. The LACMA then had Gehry design the installation for the "Treasures of Tutankhamen" exhibition in 1978 followed by the "Avant-Garde in Russia 1910–1930" exhibition in 1980. The subsequent year, Gehry designed the exhibition for "Seventeen Artists in the '60s" at the LACMA, followed soon after by the "German Expressionist Sculpture Exhibition" in 1983. In 1991–92, Gehry designed the installation of the landmark exhibition "Degenerate Art: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany", which opened at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and traveled to the Art Institute of Chicago, the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, and the Altes Museum in Berlin.[85][86] Gehry was asked to design an exhibition on the work of Alexander Calder at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art's Resnick Pavilion, again invited by the museum's curator Stephanie Barron.[87] The exhibition began on November 24, 2013, and ran through July 27, 2014.

In addition to his long-standing involvement with exhibition design at the LACMA, Gehry has also designed numerous exhibition installations with other institutions. In 1998, "The Art of the Motorcycle" exhibition opened at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum with its installation designed by Gehry. This exhibition subsequently traveled to the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao and the Guggenheim Las Vegas.

In 2014, he curated an exhibition of photography by his close friend and businessman Peter Arnell that ran from March 5 through April 1 at Milk Studios Gallery in Los Angeles.[88]

Stage design

[edit]In 1983, Gehry created the stage design for Lucinda Childs' dance Available Light, set to music by John Adams. It premiered at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles at the "Temporary Contemporary", and was subsequently seen at the Brooklyn Academy of Music Opera House in New York City and the Theatre de la Ville in Paris. The set consisted of two levels angled in relation to each other, with a chain-link backdrop.[89] The piece was revived in 2015,[90] and was performed, among other places, in Los Angeles and Philadelphia, where it was presented by FringeArts, which commissioned the revival.[91]

In 2012, Gehry designed the set for the Los Angeles Philharmonic's opera production of Don Giovanni, performed at the Walt Disney Concert Hall.

In April 2014, Gehry designed a set for an "exploration of the life and career of Pierre Boulez" by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, which was performed in November of that year.[92]

Other designs

[edit]

In addition to architecture, Gehry has made a line of furniture for Knoll and for Heller Furniture, jewelry for Tiffany & Co., various household items, sculptures, and even a glass bottle for Wyborowa Vodka. His first line of furniture, produced from 1969 to 1973, was called "Easy Edges", constructed out of cardboard. Another line of furniture released in the spring of 1992 is "Bentwood Furniture". Each piece is named after a different hockey term. He was first introduced to making furniture in 1954 while serving in the U.S. Army, where he designed furniture for the enlisted soldiers.

In many of his designs, Gehry is inspired by fish. "It was by accident I got into the fish image", claimed Gehry. One thing that sparked his interest in fish was the fact that his colleagues were recreating Greek temples. He said, "Three hundred million years before man was fish....if you gotta go back, and you're insecure about going forward...go back three hundred million years ago. Why are you stopping at the Greeks? So, I started drawing fish in my sketchbook, and then I started to realize that there was something in it."[93]

As a result of his fascination, the first Fish Lamps were fabricated between 1984 and 1986. They employed wire armatures molded into fish shapes, onto which shards of plastic laminate ColorCore are individually glued. Since the creation of the first lamp in 1984, the fish has become a recurrent motif in Gehry's work, most notably in the Fish Sculpture at La Vila Olímpica del Poblenou in Barcelona (1989–92) and Standing Glass Fish for the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden (1986).[94]

Gehry has previously collaborated with luxury jewelry company Tiffany & Co., creating six distinct jewelry collections: the Orchid, Fish, Torque, Equus, Axis, and Fold collections. In addition to jewelry, Gehry designed other items, including a distinctive collector's chess set and a series of tableware items, including vases, cups, and bowls for the company.[95]

In 2004, Gehry designed the official trophy for the World Cup of Hockey.[96] He redesigned the trophy for the next tournament in 2016.[97]

He has collaborated with American furniture manufacturer Emeco on designs such as the 2004 "Superlight" chair.[98][99]

In 2014, Gehry was one of the six "iconoclasts" selected by French fashion house Louis Vuitton to design a piece using their iconic monogram pattern as part of their "Celebrating Monogram" campaign.[100]

In 2015, Gehry designed his first yacht.[101]

In 2020, Gehry designed a limited edition bottle of Hennessy cognac.[102]

Software development

[edit]Gehry's firm was responsible for innovation in architectural software.[103] His firm spun off another firm called Gehry Technologies that was established in 2002. In 2005, Gehry Technologies began a partnership with Dassault Systèmes to bring innovations from the aerospace and manufacturing world to AEC and developed Digital Project software, as well as GTeam software. In 2014, Gehry Technologies was acquired by software company Trimble Navigation.[104] Its client list includes Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Herzog & de Meuron, Jean Nouvel, Coop Himmelb(l)au, and Zaha Hadid.

Personal life

[edit]A naturalized U.S. citizen,[105] he also remains a citizen of Canada.[106] He lives in Santa Monica, California, and continues to practice out of Los Angeles.[107] Having grown up in Canada, he is an avid fan of ice hockey. He began a hockey league, FOG (for Frank Owen Gehry), in his office, though he no longer plays with them.[108] In 2004, he designed the trophy for the World Cup of Hockey.[109]

Gehry is known for his occasional bad temper. During a trip to Oviedo, Spain to accept the Prince of Asturias Award in October 2014, he received a significant amount of attention, both positive and negative, for publicly flipping off a reporter at a press conference who accused him of being a "showy" architect.[110][111]

Gehry is a member of the California Yacht Club in Marina Del Rey, and enjoys sailing with his fiberglass-hulled yacht, Foggy.[112] He also serves on the leadership council of The New York Stem Cell Foundation.[113]

In popular culture

[edit]In 2004, Gehry voiced himself in an episode of the children's TV show Arthur, where he helped Arthur and his friends design a new treehouse.[114] He also voiced himself in a 2005 episode of The Simpsons, "The Seven-Beer Snitch", where he designs a concert hall for the fictional city of Springfield. He has since said he regrets the appearance, as it included a joke about his design technique that has led people to misunderstand his architectural process.[115]

In 2006, filmmaker Sydney Pollack made a documentary about Gehry's work, Sketches of Frank Gehry, which followed Gehry over five years and painted a positive portrait of his character; it was well-received critically.[116]

In 2009, architecture-inspired ice cream sandwich company Coolhaus named a cookie and ice cream combination after Gehry. Dubbed the "Frank Behry", it features Strawberries & Cream gelato and snickerdoodle cookies.[117][118]

Works

[edit]Exhibitions

[edit]In October 2014, the first major European exhibition of Gehry's work debuted at the Centre Pompidou in Paris.[119] Other museums and major galleries that have held exhibitions on Gehry's architecture and design include the Leo Castelli Gallery in 1983; and the Walker Art Center in 1986, whose exhibition then traveled to the Toronto Harbourfront Museum, the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, the LACMA and the Whitney Museum. Museums with exhibitions on Gehry's work have included the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art (1992), the Gagosian Gallery (1984, 1992 and 1993), the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (2001), the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao (2002), the Jewish Museum in Manhattan (2010), and the Milan Triennale (first in 1988, then in 2010 with an exhibition entitled "Frank Gehry from 1997"), and LACMA (2015).[120]

Gehry participated in the 1980 Venice Biennale's La Strada Novissima installation. He also contributed to the 1985 Venice Biennale with an installation and performance named Il Corso del Coltello, in collaboration with Claes Oldenburg. His projects were featured in the 1996 event, and contributed to the 2008 event with the installation Ungapatchket.

In October 2015, 21 21 Design Sight in Tokyo held the exhibition Frank Gehry. I Have An Idea, curated by Japanese architect Tsuyoshi Tane.[121]

In 2021, the Gagosian Gallery in Beverly Hills held Spinning Tales, an exhibition of new fish sculptures by Gehry.[122]

Awards and honors

[edit]- 1987: Fellow of American Academy of Arts and Letters

- 1988: Elected into the National Academy of Design

- 1989: Pritzker Architecture Prize

- 1992: Praemium Imperiale

- 1994: The Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize

- 1994: Thomas Jefferson Medal in Architecture

- 1995: American Academy of Achievement's Golden Plate Award[15]

- 1998: National Medal of Arts[123]

- 1998: Inaugural Austrian Frederick Kiesler Prize for Architecture and the Arts

- 1998: Gold Medal Award, Royal Architectural Institute of Canada

- 1999: AIA Gold Medal, American Institute of Architects

- 2000: Cooper–Hewitt National Design Award Lifetime Achievement[124]

- 2002: Companion of the Order of Canada (CC)[125]

- 2004: Woodrow Wilson Award for Public Service

- 2006: Inductee, California Hall of Fame

- 2007: Henry C. Turner Prize for Innovation in Construction Technology from the National Building Museum (on behalf of Gehry Partners and Gehry Technologies)

- 2009: Order of Charlemagne

- 2012: Twenty-five Year Award, American Institute of Architects

- 2014: Prince of Asturias Award

- 2014: Commandeur of the Ordre National de la Légion d'honneur, France

- 2015: J. Paul Getty Medal

- 2016: Harvard Arts Medal

- 2016: Leonore and Walter Annenberg Award for Diplomacy through the Arts, Foundation for Arts and Preservation in Embassies

- 2016: Presidential Medal of Freedom

- 2018: Neutra Medal[126]

- 2019: Inductee, Canada's Walk of Fame

- 2020: Paez Medal of Art, New York City (VAEA)[127]

Gehry was elected to the College of Fellows of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) in 1974,[128] and he has received many national, regional and local AIA awards. He is a senior fellow of the Design Futures Council and serves on the steering committee of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture.

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| |

Honorary doctorates

[edit]- 1987: California Institute of the Arts

- 1987: Rhode Island School of Design

- 1989: Otis College of Art and Design

- 1989: Technical University of Nova Scotia

- 1993: Occidental College

- 1995: Whittier College[131]

- 1998: University of Toronto

- 2000: Harvard University

- 2000: University of Edinburgh

- 2000: University of Southern California

- 2000: Yale University

- 2002: City College of New York

- 2004: School of the Art Institute of Chicago

- 2013: Case Western Reserve University

- 2013: Princeton University

- 2014: Juilliard School

- 2015: University of Technology Sydney

- 2017: University of Oxford

- 2019: Southern California Institute of Architecture[132]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

- ^ "Great modern buildings: Frank Gehry biography". The Guardian. October 8, 2007. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ^ a b Tyrnauer, Matt (June 30, 2010). "Architecture in the Age of Gehry". Vanity Fair. Retrieved July 22, 2010.

- ^ for the design, see: "Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial: Design" Archived November 19, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Filler, Martin (2007). Makers of Modern Architecture. New York Review Books. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-59017-227-8. OCLC 82172814.

- ^ Emanuel, Muriel, ed. (1994). Contemporary Architects (3rd ed.). St. James Press. pp. 341–343. ISBN 1-55862-182-2. OCLC 30816307.

- ^ a b c Chollet, Laurence B. (2001). The Essential Frank O. Gehry. New York: The Wonderland Press. p. 112. ISBN 0-8109-5829-5.

- ^ Finding Your Roots, February 2, 2016, PBS

- ^ Green, Peter S. (June 30, 2005). "In the News: Warsaw Jewish Museum In Poland". The New York Times. Retrieved August 30, 2011.

- ^ Gorin, Abbott (Spring 2015) "A Golden Age of Jewish Architects" Jewish Currents. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ Ouroussoff, Nicolai (October 25, 1998) "I'm Frank Gehry, and This Is How I See the World"[dead link] https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1998-oct-25-tm-35829-story.html Los Angeles Times Magazine

- ^ a b c Templer, Karen (December 5, 1999). "Frank Gehry". Salon. Retrieved August 25, 2007.

- ^ Lacayo, Richard; Levy, Daniel S. (June 26, 2000). "Architecture: The Frank Gehry Experience". Time. Vol. 155, no. 26. p. 64. Archived from the original on January 5, 2013. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- ^ Reinhart, Anthony (July 28, 2010). "Frank Gehry clears the air on fishy inspiration". The Globe and Mail. ProQuest 2385608064. Archived from the original on July 31, 2010.

- ^ Verge, Stéphanie (July 2022). "Frank Talk". Toronto Life. p. 55:

Gehry's a phony name—I changed it in 1954 because my ex-wife was worried about antisemitism and thought it sounded less Jewish.

- ^ a b "Biography and Video Interview of Frank Gehry at Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ Engel, Eliot L. (August 2, 2013). "Congratulating the Alpha Epsilon Pi International Fraternity". Capitol Words. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- ^ Schoenberg, Jeremy (January 18, 2011) "Architect Frank Gehry Named Judge Widney Professor" Archived October 23, 2022, at the Wayback Machine USC News

- ^ Isenberg, Barbara (2012). Conversations with Frank Gehry. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 40–43. ISBN 978-0-307-95972-0.

- ^ Ray, Debika (February 27, 2020). "As architect Frank Gehry turns 90 years old we look back at his prolific career". ICON Magazine. Retrieved December 19, 2024.

- ^ Sisson, Patrick (August 21, 2015). "21 First Drafts: Frank Gehry's David Cabin". Curbed. Archived from the original on January 7, 2017. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- ^ Goldberger (2015), pp.110–111

Lazo, Caroline Evensen (2006) Frank Gehry. Twenty-First Century Books

Hawthorne, Christopher (October 8, 2014) "In Paris, a Passion for All Things Frank Gehry" Los Angeles Times - ^ Gehry Partners, LLP website Archived December 19, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Molloy, Jonathan C. (February 28, 2013). "AD Classic: Norton House / Frank Gehry". ArchDaily.com. Retrieved May 25, 2013.

- ^ Head, Jeffrey (October 21, 2009). "Frank Gehry: The Houses". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Gehry House – Frank Gehry". Great Buildings Collection. Retrieved June 3, 2010.

- ^ "Jury Citation: Frank Gehry: 1989 Laureate". pritzkerprize.com. Pritzker Architecture Prize. 1989. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ Colwell, Hailey (August 5, 2015). "Modeling the museum for 17 years". Weisman.UMN.edu. The Frederick Weisman Museum of Art, University of Minnesota. Archived from the original on May 10, 2006. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ "American Center, Paris". galinsky.com. 2010. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ "Architect March 2010 Page 80". lscpagepro.mydigitalpublication.com. Retrieved August 19, 2024.

- ^ "Dancing House". galinsky.com. 2006. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ Tyrnauer, Matt (August 2010). "Architecture in the Age of Gehry". Vanity Fair. Retrieved March 27, 2012.

- ^ Roston, Eric (October 11, 2004). "Windy City Redux". Time. Archived from the original on September 9, 2009. Retrieved July 30, 2008.

- ^ Hawthorne, Christopher (September 21, 2013). "Frank Gehry's Walt Disney Concert Hall is inextricably of L.A." Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- ^ Hawthorne, Christopher (January 24, 2011). "Architecture review: Frank Gehry's New World Center in Miami Beach". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "The Stata Center". MIT.edu. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ Cliatt, Cass (September 11, 2008). "Architect Gehry seeks to inspire with Princeton's Lewis Library design". Archived from the original on March 8, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ Staff. "Experience Music Project". Fodors. Archived from the original on August 18, 2010. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- ^ Ouroussoff, Nicolai (March 22, 2007). "Gehry's New York Debut: Subdued Tower of Light". The New York Times. Retrieved August 25, 2007.

- ^ Ouroussoff, Nicolai (February 9, 2011). "8 Spruce Street by the Architect Frank Gehry – Review". The New York Times.

- ^ "UTS City Campus Master Plan". uts.edu.au. University of Technology Sydney. Archived from the original on September 3, 2014. Retrieved August 30, 2014.

- ^ Gilmore, Heath (August 30, 2014). "Frank Gehry's Sydney building sculpture revealed". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved August 30, 2014.

- ^ "Projects by Nouvel and Gehry Finally Moving Forward on Saadiyat Island". Architectural Record. January 26, 2011. Retrieved August 30, 2011.

- ^ Bozikovic, Alex (December 7, 2013). "Frank Gehry and David Mirvish's Tall Order in Toronto". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved December 8, 2013.

- ^ "Superstar Architects Gehry and Foster to design Battersea Power Station's High Street". PrimeResi.com. October 23, 2013. Retrieved October 23, 2013.

- ^ Tommasini, Anthony (December 7, 2013). "Arts Hub for All May Work for None". The New York Times. Retrieved December 8, 2013.

- ^ Pogrebin, Robin (February 6, 2012). "Eisenhower as Barefoot Boy? Family Objects to a Memorial". The New York Times.

- ^ Campbell, Robert (October 13, 2012). "Pressing Pause, for Cause, On the Eisenhower Memorial". Boston Globe.

- ^ Kennicott, Philip (December 17, 2011). "Review: Frank Gehry's Eisenhower Memorial reinvigorates the genre". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

- ^ "The Biomuseo, the great works of Frank Gehry". VisitPanama.com. Archived from the original on June 5, 2012. Retrieved August 30, 2011.

- ^ "Eliasson show due to open Paris' Louis Vuitton museum". Collector Tribune. March 26, 2012. Retrieved October 21, 2012.

- ^ "Foundation Louis Vuitton: Frank Gehry". arcspace.com. January 8, 2007. Archived from the original on June 18, 2012. Retrieved August 30, 2011.

- ^ Riding, Alan (October 3, 2006). "Vuitton Plans a Gehry-Designed Arts Center in Paris". The New York Times. Retrieved August 30, 2011.

- ^ Kennicott, Philip (September 2014). "Gehry's Paris Coup". Vanity Fair. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- ^ Hawthorne, Christopher (August 9, 2015). "Frank Gehry agreed to make over the L.A. River – with one big condition / How Frank Gehry's L.A. River make-over will change the city and why he took the job". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 13, 2015. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ "Frank Gehry's controversial L.A. River plan gets cautious, low-key rollout". Los Angeles Times. June 18, 2016. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved July 27, 2017.

- ^ "Frank Gehry says his 'crumpled paper bag' building will remain a one-off". The Guardian. Australian Associated Press. February 2, 2015. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ^ Dreyfus, Stéphane (November 4, 2016). "Frank Gehry, 'l'art-chitecte'". La Croix.

- ^ a b Perlson, Hili (November 15, 2016). "With Trump Elected, Frank Gehry Wants to Move to France". Artnet News.

- ^ La Rose, Lauren (December 3, 2016). "Architect Frank Gehry 'very worried' about Donald Trump". ctvnews.ca. Toronto. The Canadian Press. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ "Donald Trump versus Frank Gehry". Los Angeles Times. 2016. Archived from the original on August 14, 2015. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ Kennicott, Philip (August 5, 2020). "The new Eisenhower Memorial is stunning, especially at night. But is this the last of the 'great man' memorials?". Washington Post. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

- ^ Hickman, Matt (June 28, 2021). "Luma Arles opens in Provence with all eyes on Frank Gehry's polarizing centerpiece". The Architect's Newspaper. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

- ^ Volner, Ian (September 17, 2021). "Frank Gehry moved to Los Angeles 75 years ago; it's only now coming around to his brand of wily artistry". The Architect's Newspaper. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

- ^ a b Power, Julie (February 6, 2015). "Frank Gehry: the Mad Hatter who transformed Sydney's skyline". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved September 12, 2017.

- ^ a b "Frank Owen Gehry". achille.paris. May 28, 2015. Archived from the original on November 19, 2015. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ^ "The weird architectural world of Frank Gehry". WorldBuild365. March 29, 2017. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- ^ Adams, B. (1988) "Frank Gehry's Merzbau". Art in America 76: pp.139–144

- ^ Isenberg, Barbara S.; Gehry, Frank O. (2009). Conversations with Frank Gehry. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-307-26800-6.

- ^ Isenberg, Barbara S.; Gehry, Frank O. (2009). Conversations with Frank Gehry. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-307-26800-6.

- ^ Rybczynski, Witold (September 2002). "The Bilbao Effect". The Atlantic. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ Horn, Eli (December 25, 2014). "Bilbao's Economy Purrs From Effect of Guggenheim Museum". Jewish Business News. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ Rybczynski, Witold (November 22, 2008). "When Buildings Try Too Hard". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ a b Taylor-Foster, James (December 8, 2013). "Frank Gehry: 'I'm Not a Starchitect'". Archdaily.com. Retrieved December 8, 2013.

- ^ Flyvbjerg and Gardener, Bent and Dan (January–February 2023). "How Frank Gehry Delivers on Time and on Budget".

- ^ Gilbert-Rolfe, Jeremy; Gehry, Frank O. (2002). Frank Gehry: The City and Music. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-23995-0.

- ^ Foster, Hal (August 23, 2001). "Why all the hoopla?". London Review of Books. Vol. 23, no. 16. Retrieved August 30, 2011.

- ^ Favermann, Mark (November 7, 2007). "MIT Sues Architect Frank Gehry Over Flaws at Stata Center". Berkshire Fine Arts. Retrieved August 30, 2011.

- ^ Speck, Jeff (2012)Walkable City: How Downtown Can Save America, One Step at a Time New York: North Point Press. pp.243–45. ISBN 978-0-86547-772-8

- ^ Vincent, Roger (March 17, 2017). "There's another Frank Gehry building going up in town. It's under the radar in El Segundo". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ^ Cocotas, Alex (June 2016). "Design for the one percent". Jacobin. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- ^ USC News (January 18, 2011). "Architect Frank Gehry Named Judge Widney Professor (press release)". Archived from the original on January 22, 2011. Retrieved January 18, 2011.

- ^ "Frank O. Gehry" Archived February 18, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Yale School of Architecture website

- ^ "Frank Gehry: 'Don't Call Me a Starchitect'". The Independent. December 17, 2009. Archived from the original on June 21, 2017. Retrieved December 8, 2013.

- ^ Kaller, Hadlet (February 17, 2017). "Now Anyone Can Take a Class with Frank Gehry". Architectural Digest. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ^ Muchnic, Suzanne (February 6, 1992), "LACMA 'Degenerate' Exhibit to Make a Stop in Germany" Los Angeles Times

- ^ Wilson, William (February 15, 1991) "Revisiting the Unthinkable: Nazi Germany's 'Degenerate Art' Show at LACMA" Los Angeles Times

- ^ Fleishman, Jeffrey (February 28, 2014) "Frank Gehry and Alexander Calder, a captivating union at LACMA" Los Angeles Times

- ^ "When Architects Curate: Frank Gehry's Peter Arnell Retrospective at Milk Studios | Object Lessons". Blouin Artinfo. Archived from the original on April 15, 2014. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ^ Lazar, Julie (1983) "Interview: Frank Gehry" in Available Light Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. ISBN 0-914357-01-8

- ^ Lazar, Julie (June 3, 2015) "'Available Light' Returns to the Stage After Three Decades" KCET

- ^ "Available Light" Archived December 20, 2016, at the Wayback Machine FringeArts

- ^ Staff (April 23, 2014). "Architect Frank Gehry to Create Set Design for Chicago Symphony Orchestra Focused on Pierre Boulez". Broadway World. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ^ Pollack, Sydney (dir.) (1985) American Masters: Sketches of Frank Gehry (TV documentary) Archived June 16, 2017, at the Wayback Machine PBS. access-date=2008-11-17

- ^ "Frank Gehry: Fish Lamps, November 7 – December 21, 2013" Archived November 11, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Gagosian Gallery, London

- ^ "Frank Gehry's Tiffany Chess Set Is a Miniature Architectural Marvel". Gizmodo. April 28, 2012. Archived from the original on July 5, 2017. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ^ Adams, Noah (September 3, 2004). "Frank Gehry's World Cup of Hockey Trophy". The New York Times. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- ^ Seravalli, Frank. "World Cup of Hockey Trophy Gets a Facelift". The Sports Network. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ^ "Superlight chair". SFMOMA. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ^ "Emeco Designers – Frank Gehry". Emeco Industries Inc. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ^ "Louis Vuitton: Celebrating Monogram Project". celebrating.monogram.lv. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ^ Ward, Vicky (October 5, 2015). "Frank Gehry's First-Ever Yacht Looks Like Nothing You've Ever Seen". Town & Country. Retrieved October 13, 2015.

- ^ Ravenscroft, Tom (September 25, 2020). "Frank Gehry forges crinkled gold bottle to mark 150th anniversary of Hennessy X.O". Dezeen. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

- ^ Appelbaum, Alec (February 11, 2009). "New York Times: Frank Gehry's Software Keeps Buildings on Budget". The New York Times. Retrieved December 13, 2012.

- ^ Ferro, Shaunacy (September 11, 2014), Frank Gehry's Software Company Acquired Fast Company.

- ^ Phillips, Susan P. (2014). Displays!: Dynamic Design Ideas for Your Library Step by Step. McFarland. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-7864-8707-3.

- ^ LaRose, Lauren (December 3, 2016) "Canadian-American architect Frank Gehry 'very worried' about Donald Trump" iPolitics

- ^ "Gehry Partners, LLP" Archinect

- ^ Goldberger (2015)

- ^ Baurick, Tristan (May 13, 2004). "Architect's love of the game inspiration behind Cup trophy", Ottawa Citizen, p. C2.

- ^ Schledahl, Peter (October 27, 2014). "Frank Gehry's Digital Defiance". The New Yorker. Retrieved October 27, 2014.

- ^ McKenny, Leesha (October 27, 2014). "Frank Gehry gives the finger in response to accusations of "showy architecture"". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved October 27, 2014.

- ^ Browne, Alix (April 19, 2009). "Love for Sail". The New York Times. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ^ "Leadership Council". New York Stem Cell Foundation. Archived from the original on May 19, 2015. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ^ Booth, John (October 10, 2011). "The 15 Geekiest Episodes of PBS's Arthur". Wired. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ^ Chaban, Matt (September 5, 2011). "Frank Gehry Really, Really Regrets His Guest Appearance on The Simpsons". The New York Observer. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ Sketches of Frank Gehry. Rotten Tomatoes.

- ^ Staff (May 20, 2014). "How to Construct an Epic Ice Cream Sandwich Like an Architect". Food & Wine. Archived from the original on October 29, 2014. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ Coolhaus (December 2, 2009). "Frank Behry Tribute Video!". Blogspot. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ Giovannini, Joseph (October 20, 2014). "An Architect's Big Parisian Moment Two Shows for Frank Gehry, as His Vuitton Foundation Opens". The New York Times. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- ^ "Frank Gehry – LACMA". Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Archived from the original on October 15, 2015. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ Balboa, Rafael A.; Scaroni, Federico (November 4, 2015). "Frank Gehry: I have an idea". domusweb.it. Editoriale Domus Spa. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ Reiner-Roth, Shane (July 7, 2021). "Frank Gehry's Spinning Tales shows off new sculptures at the Beverly Hills Gagosian gallery". The Architect's Newspaper. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

- ^ "Lifetime Honors – National Medal of Arts". National Endowment for the Arts. Archived from the original on August 6, 2011. Retrieved August 30, 2011.

- ^ "Lifetime Achievement Winner: Frank Gehry". Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Archived from the original on September 25, 2010.

- ^ "Companion of the Order of Canada". Governor General of Canada. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ^ "Neutra Award | Department of Architecture | College of Environmental Design – Cal Poly Pomona".

- ^ "FRANK GEHRY is one of the two recipient of VAEA's Paez Medal of Art 2020". VAEA. Archived from the original on October 27, 2021. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- ^ "Frank Owen Gehry (Architect)". Pacific Coast Architecture Database. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ "Frank Gehry: My days as a young rebel". TED Talks. 1990. Retrieved September 29, 2015.

- ^ "Frank Gehry: A master architect asks, Now what?". TED Talks. 2002. Retrieved September 29, 2015.

- ^ "Honorary Degrees | Whittier College". www.whittier.edu. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- ^ "Honorary Degrees | SCI-Arc Presents World-Renowned Architect Frank Gehry with Honorary Degree". www.sciarc.edu. Retrieved October 1, 2019.

Bibliography

[edit]- Dal Co, Francesco; Forster, Kurt W.; Arnold, Hadley (1998). Frank O. Gehry: The Complete Works. New York: The Monacelli Press. ISBN 978-1-885254-63-4.

- Gehry, Frank O.; Colomina, Beatriz; Friedman, Mildred; Mitchell, William J.; Ragheb, J. Fiona; Cohen, Jean-Louis; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum; Museo Guggenheim Bilbao (May 2001). Frank Gehry Architect (Hardcover). Guggenheim Publications. p. 390. ISBN 978-0-8109-6929-2.

- Goldberger, Paul (2015). Building Art: The Life and Work of Frank Gehry. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-307-70153-4. OCLC 913514521.

- Rattenbury, Kester (2006). Architects Today Laurence King Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85669-492-6.

- Staff (1995). "Frank Gehry 1991-1995". El Croquis.

Further reading

[edit]- Bletter, Rosemarie Haag; Walker Art Center (1986). The Architecture of Frank Gehry. New York: Rizzoli. ISBN 0-8478-0763-0. ISBN 978-0-8478-0763-5.

- Sorkin, Michael (December 17, 1999). Friedman, Mildred (ed.). Gehry Talks: Architecture + Process (Hardcover) (1st ed.). New York: Rizzoli. ISBN 978-0-8478-2165-5.

- Gehry, Frank O. (2004). Gehry Draws. Violette Editions. ISBN 978-1-900828-10-9.

- Richardson, Sara S. (1987). Frank O. Gehry: A Bibliography. Monticello, Ill.: Vance Bibliographies. ISBN 1-55590-145-X.

- van Bruggen, Coosje (December 30, 1999) [1997]. Frank O. Gehry: Guggenheim Museum Bilbao (Hardcover) (1st ed.). New York: Guggenheim Museum Pubns. ISBN 978-0-8109-6907-0.

External links

[edit]- Gehry Partners, LLP, Gehry's architecture firm

- Gehry Technologies, Inc., Gehry's technology firm

- Frank Gehry at TED

- Frank Gehry on Charlie Rose

- Frank Gehry at IMDb

- Frank Gehry collected news and commentary at The Guardian

- Frank Gehry collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- Fish Forms: Lamps by Frank Gehry Exhibition (2010) at The Jewish Museum (New York)

- STORIES OF HOUSES: Frank Gehry's House in California

- Bidding for the National Art Museum of China's new site

- Gehry Draws on Violette Editions

- Frank Gehry architecture on Google Maps

- CS1: unfit URL

- 1929 births

- Architects from Los Angeles

- Art in Greater Los Angeles

- 20th-century Canadian architects

- Canadian furniture designers

- Canadian emigrants to the United States

- Canadian male voice actors

- Canadian Jews

- Canadian people of Polish-Jewish descent

- Columbia University faculty

- Companions of the Order of Canada

- Deconstructivism

- Harvard Graduate School of Design alumni

- Jewish architects

- Jewish American artists

- Living people

- Members of the European Academy of Sciences and Arts

- National Design Award winners

- Organic architecture

- Architects from Toronto

- Postmodern architects

- Pritzker Architecture Prize winners

- Recipients of the Praemium Imperiale

- Recipients of the Royal Gold Medal

- United States Army soldiers

- United States National Medal of Arts recipients

- USC School of Architecture alumni

- Wolf Prize in Arts laureates

- Yale School of Architecture faculty

- People associated with the Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Honorary members of the Royal Academy

- American people of Polish-Jewish descent

- 20th-century American architects

- 21st-century American architects

- 21st-century Canadian architects

- American furniture designers

- American male voice actors

- 21st-century American Jews

- Recipients of the AIA Gold Medal

- Fellows of the American Institute of Architects